Article

Rules-based versus Principal-based Evaluation methods

Health technology assessment (HTA) is a tool used to determine whether new medicines or devices provide good economic value to healthcare systems. Any chosen methodology of evaluation will fit somewhere on a spectrum between being purely rules-based (RB) and purely principle-based (PB). RB approaches tend toward being guided by a strict set of pre-specified rules that don’t typically allow for contextual relevance and that may often exclude aspects of impact or value specific to any one technology or disease area. Alternatively, a PB approach greets each new technology being evaluated with its own uniquely relevant method that incorporates all potential aspects of the specific technology, but because of this specificity will have limited value in terms of generalized comparison to ‘other’ technologies (or disease areas).

This gets at the major tension between RB and PB evaluation methods with respect to technology evaluation in terms of its two main goals. The first is to, where possible, always come to the right answer (A). The second is to be seen to be treating each question, or technology, the same (B). While it may seem that there must be a way to achieve both goals simultaneously, in truth, as any methodology gets more detailed, uses more data and addresses a wider set of stakeholders, the tension between the two competing goals only rises. As a result, a perfect, one-size-fits-all approach to value assessment probably does not exist. The more you try to generalize a method for the goal of B, the less accurate it will be for each individual technology, or disease, in its attempt to achieve A.

Thus, there is a tendency for the evolution of the approach taken to favor one goal over the other, or to bend towards one pole as it evolves over time, rather than attempt the much more difficult, nay impossible, feat of addressing both goals equally.

In most ex-US countries, where single-payer systems dominate, HTA methods have steered strongly towards rules-based methods. In the US there is a plethora of different evaluation methods (four tools in oncology alone), but the fact that there are many, and that there is no formal single method used here, suggests that overall the US has a stronger PB ethos.

Principle versus rules-based taxonomy

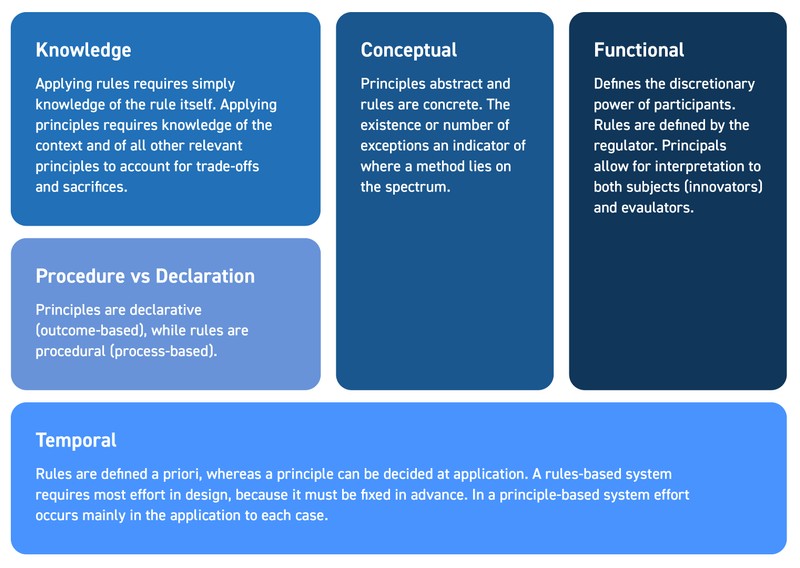

There are certain characteristics that delineate the poles of ‘pure’ RB and PB. Firstly, implementation of a PB system requires a significant level of knowledge and expertise about the subject matter in question – the disease, the treatment’s mechanism of action, the treatment landscape, and the population of need, to name a few. Moreover, adoption of one principle often involves a trade-off with another principle. For example, the desire to optimize potential benefits may compromise the desire to minimize risks around adverse events. Solving such dilemmas across very different disease landscapes often requires a different kind of reasoning than straightforward application of rules. For instance, the previously mentioned example of four oncology value tools which all weight survival gains and adverse events slightly different. Burgemeestre and colleagues (2009) provide a helpful structure for defining the differences (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Five Differentiating Dimensions of RB vs PB Evaluation Methods

RB: rules-based; PB: principles-based

PB evaluation is more geared towards specificity and truth – the desire is to get as close to the real answer as possible, which may mean using outcomes, or a framework of assessment, that best represents the specific patient group, disease or technology type under study. RB methods tend to put consistency above specificity; the ability to use the same approach for all technologies trumps any need to address the specific nuances of novel technologies that may not fit into a standard framework. Such RB methods risk becoming outdated absent regular updates and revisions as the context constantly evolves. This is not to say that RB methods cannot evolve or change, but that the incentive to change is low (as any change risks making it become more PB, and as a result increasing the knowledge required to make informed valuation decisions). As a result, the need to gain full acceptance to replace one set of rules with another set means the speed of any successful evolution in a RB approach will tend to be slow.

For example, if it was agreed that as a result of the recent emergence of gene therapies, or precision medicine, these treatments needed to be viewed from a different lens to be adequately accredited or understood, a PB system would be more likely to nimbly evolve to address these technological evolutions, whereas a RB system would require a level of consensus and a formal agreement on each change applied that would likely require considerable time, meaning for years, or perhaps decades, these new technologies would remain at a disadvantage to more conventional technologies, hindering the speed of innovation. In fact, this has been partially borne out in the data; Tunis et al (2021) found that although there have been similar rates of regulatory approval of cell and gene therapies in the US and Europe, US plans were more likely to cover access to these therapies than EU5 and Canadian HTA bodies. This is in spite of the fact that countries with a single-payer health care system have more to gain from covering these therapies as they accrue the long run benefits of having a one and done therapy more so than an individual insurance company in the US.

There are inevitable trade-offs between the RB and PB approaches when it comes to evaluating new medicines, but over the history of HTAs globally approaches that started out with a foot in each camp have been strongly steered, by circumstance or design, towards RB. The question that we are faced with is as both medicines, and healthcare technologies more widely evolve and our understanding of how these innovations impact complex multifaceted healthcare systems in different ways, is whether a shift back towards a place where the benefits of PB are more obviously recognized is a necessity if we want to capture true value.

Read Part 1